My practice draws on an academic background in historical studies, a life spent in rural Cumbria, an adulthood curiosity about both the natural world and the way humans interact with it. Travel is an obsession which first took me to Arctic Norway in 2018. Since then most of my writing has focused on this seascape of fishing, decline and the symbiotic relationship between people and eiders.

While this place remains at the heart of my current practice, I’m also beginning to question what we consider ‘poetry’—which runs alongside the increasing visual art influence within my freelance projects.

Publications include The Arctic Diaries (2023); Between The Trees (2023); New Writing North West (2022); Solstice Shorts (2021).

Fiskebruk

He’s explaining the fiskebruk

but all I can think about is the fisherman’s

filleting knife slipping under my epidermis

flicking individual bones out in experienced

exquisite rhythm.

From The Arctic Diaries

physical immersion

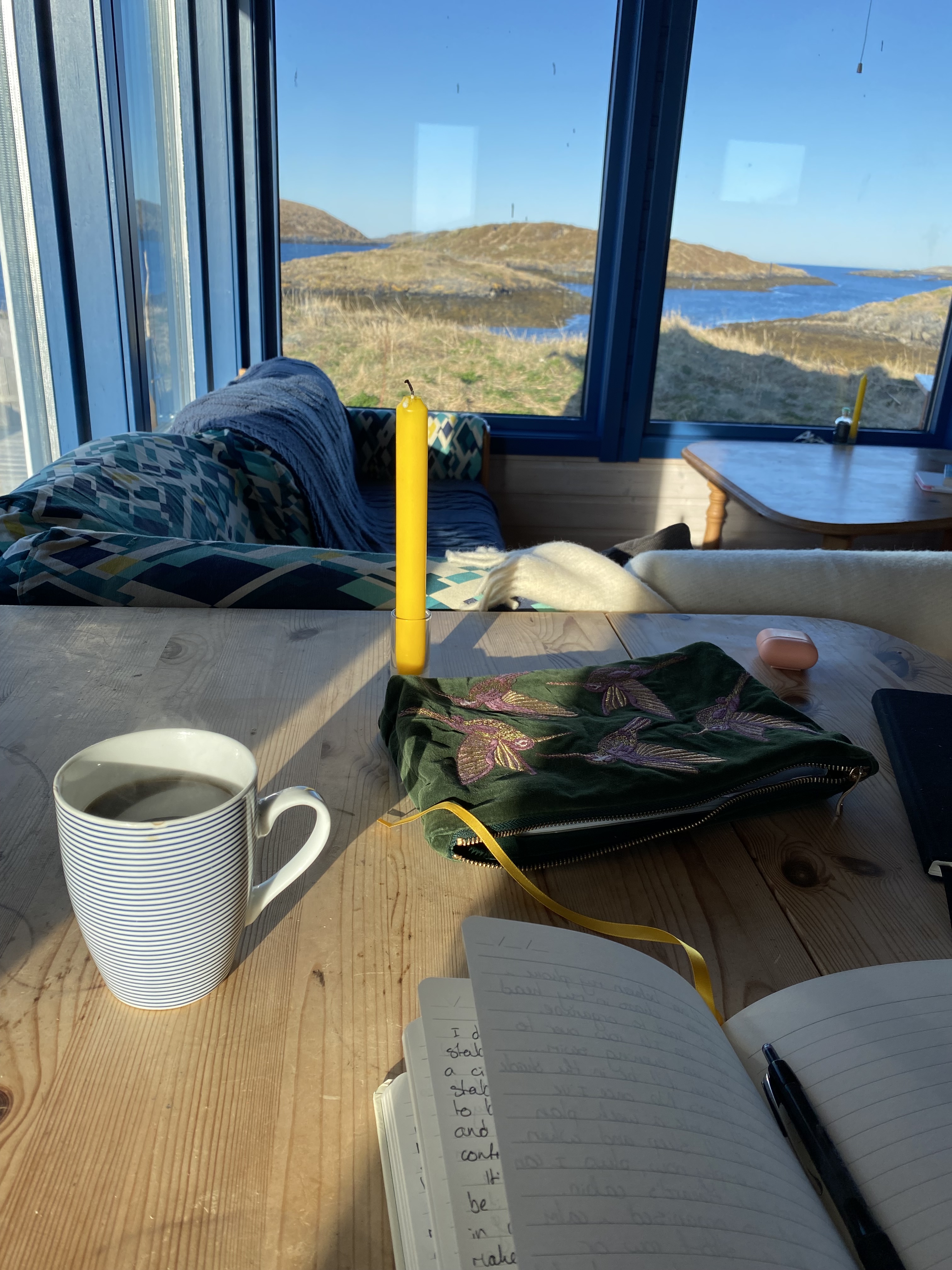

Thanks to ACE’s Develop Your Creative Practice funding, I will explore the physical act of writing and how immersion in the landscape of Malcom of Løksyøya impacts the poems inspired by his life.

Collage

Past material has included employment contracts, newspaper articles and public responses to a prompt. My current explorations manipulate everyday conversation with lineation and collage.

Preservation

I continue to explore poetry as a method of preserving oral traditions from the Norwegian archipelago of Fleinvær. This practice investigates what folk stories tell us about the impact of environmental change on seascapes.

Extract from ‘Vanishing Act’

‘These stories of sunfish are pulled from hats

of salt-dumb old men while their fingers

finger rings from crab pots and your children disappear.

How can you know what you will feel

when it’s over? Grief as the last spectator leaves,

relief that your son will never learn to make one skrei

feed four children when only half the shoal reappear.

Your eagle’s eyrie is a pile of sticks

every needle bone must be collected before they bend,

while you can still see whole animal bodies.’